I recently had the great fortune to acquire an article first printed in 1930 in ‘The Colophon” a limited edition quarterly for book lovers, , in which Hugh Walpole gives the back story on how he managed to secure his first publication.

What an excitement it must have been for Hugh, who from a young age had been determined to become a professional writer, to receive his first acceptance from a publisher.

Here is Hugh’s account of the occasion in his own words from that very article with a few additional illustrations I’ve added to set the scene.

My First Published Book, By Hugh Walpole

Into what distant ages do I look back and to what supreme and unjustified confidence! I gather, however, that this account is intended to be practical rather than sentimental. If I can I will recover the facts but – how difficult the facts are after all these years, and how shadowy their outlines!

Of one thing at least I can be sure. That I had been writing novels ever since I was six, and of another fact also that I never had the slightest doubt but that one day I would be published. Now why I was so cer- tain I can’t conceive. No one else had the very slightest confidence in me. There was very little “writing” at that time in the fami- ly. Later on my father published works of theology, and very good some of them were, but my father never cared so very greatly for the arts. His impulse was quite another.

No one encouraged me to read, to care for pictures and music. I had no literary relations unless you can call a two-century uncle, Horace Walpole, or a fifty-year distant uncle, Barham of the Ingoldsby Legends, relations. And yet I wrote as I breathed, in quite the old-fashioned way-as indeed I have done ever since

My taste, from six to twenty, was for historical romances. I read them passionately and I wrote them passionately. I read Scott then for the story-the absence of which is, I understand, the reason why no one reads him today. And yet today no one cares for story. Why should he not be read then for character, his supreme claim? Perhaps soon again he will be. Shades also of Francis Marion Crawford and Stanley Weyman, let me pay you this transient tribute! What reassurance you gave to at least one unhappy and bewildered childhood! And even now I dare to assert that Saracinesca and St. Ilario, The Castle Inn and Count Hannibal, are beyond the present powers of any living novelist whether of England or America.

So, under every constant evidence of disapproval, I wrote my romances, wrote them, bound them in brown paper and put them away. I had then the true “writer’s fervor”. I didn’t care whether anyone read them or no. I wrote only for my own delight.

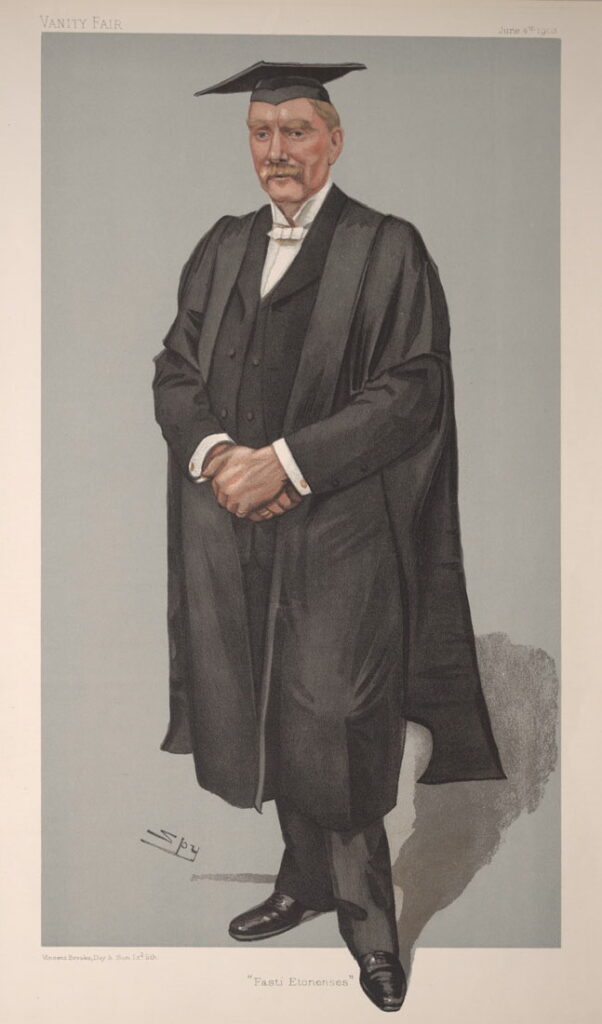

Then, during my last year at school and my first year at Cambridge, I wrote a long modern story and called it Troy Hanneton. Only one living person ever saw it, Arthur Christopher Benson, a friend of my father’s, a very loyal friend of my own. He read it (or part of it – it was in my own atrocious handwriting), wrote me a kind letter advising me to destroy it, urging me to read the works of George Moore, and finally with great kindness advising me to put novel writing out of my head, as novelist I was not, nor ever would be!

Now here was an odd thing. I never in my life had such an incentive to continue novel-writing as from this letter of Benson’s. I cannot explain it, but I knew after reading that letter of Benson’s that I was a novelist and that nothing henceforward would stop me. It was not that I did not value Benson’s opinion (I at once followed his advice and burnt Troy Hanneton), but his reasons against my being a novelist seemed to me all the wrong ones. I still think they were.

I began at once another novel entitled The Abbey. At this I strove for a year. It was my first attempt at a full-grown novel – not, as Troy was, rather plaintive autobiography

By the end of a year I was in so desperate a confusion, so many characters were driving aimlessly in so many different directions, that I had to abandon it, but it has this interest for me, that the ten odd chapters of it held the germ of a book published nearly twenty years later, The Cathedral.

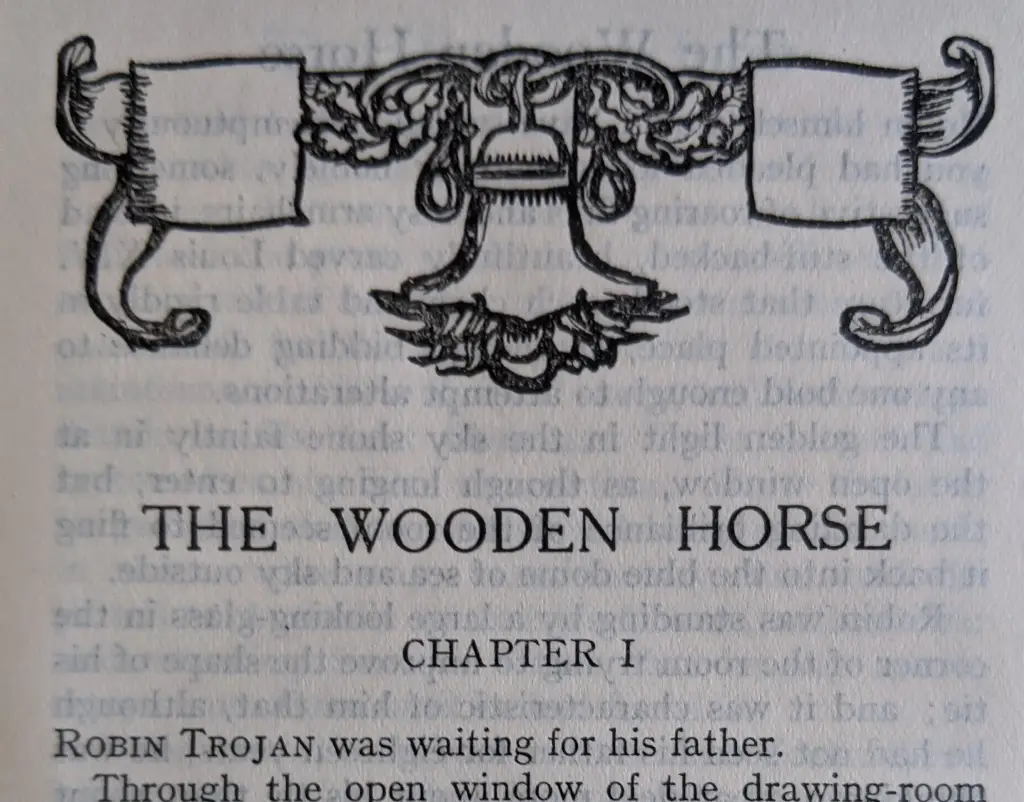

I abandoned it and began another – The Wooden Horse. I was at this time for my sins a schoolmaster, and when I had written the first half of the book I showed it to a fellow schoolmaster, a man much older than myself, of whose abilities I had the greatest opinion. He read it and returned it to me, saying sorrowfully that whatever else I might be I was not a novelist.

This again did not in the slightest deter me. I finished the thing, abandoned school mastering and came up to London with thirty pounds in all the world and not the least prospect of a job anywhere.

Indeed I have reason now, with my fuller knowledge, to marvel at my hardihood. I did not, I must honestly admit, think that The Wooden Horse was a masterpiece. I suffered then, as I still suffer, from the shabby fashion in which characters who have been living with you in close intimacy for years vanish into air as soon as the word “Finis” is written on the final page.

It is my longing to recover some of their company. I suppose that has led me so often to drag characters by the hair of their heads from one book into another-a most reprehensible proceeding, but one that will, I suppose, carry on to the last. They were alive once-why should they not be alive again? And, sometimes, they do return.

I had no illusions about The Wooden Horse. I have, I think, never had any illusions about any book of mine. Only after a great distance of time do you recover an affection for them. I knew that this book had no importance, but I also knew that between The Abbey and this I had in some mysterious way stepped from the amateur to the young professional. Too much the professional. I fancy that only now, twenty years after, I am recovering some of the amateur again, but that too may be illusion.

In any case I had a friend and I sent him my book. This friend is the only man, as I think, who has ever written about Cornwall as a poet should. Charles Marriott is his name; he was once a novelist, is now art critic for the London Times. His novels The Column, Genevra, The Catfish and others will be rediscovered one day. His prose can- not be lost: he writes about Cornwall like an inspired angel. In any case his was the first encouragement I ever received, and I’ll never forget my debt. He said kind things, wise things, cautionary things.

I showed it also, I remember, to E. M. Forster, whom I had met in Germany. He was then at the beginning of his grand career, and he is as modest and gentle now as he was modest and gentle then. He can’t have liked The Wooden Horse very much, I imagine, but he said what he could. At any rate he read it and said that it should be published.

I can see him now, long, shambling and shy, looking beyond me into some space of his own (and he has always occupied a room entirely of his own; he has another room for visitors and he very often isn’t there when they think that he is), trying to tell me some of the things that my book ought to have. He couldn’t, of course; no one ever can. But I was grateful, and he was, I am sure, intensely glad when the little matter was closed.

But, thus encouraged, I had no hesitation now in approaching a publisher. I would, I thought, begin at the top and work my way down the list. The top for me at that time was the publisher of Thackeray and the Brontës, the firm of Smith Elder, now defunct. The original Mr. Smith was one of my heroes, for had he not been kind to Charlotte and soothed the nerves of William Makepeace? So I scraped my shillings together, The Wooden Horse was typed, done up in brown paper, fastened with pink string (I remember very clearly how my Chelsea landlady, Mrs. King, a little woman with long legs like a sparrow on stilts, did this part of the job for me) and sent it off.

I sat down then and waited. I had managed, with my usual luck, to receive some reviewing on the Standard newspaper, and for this I received three pounds a week. I was then perfectly happy in my two basement rooms in Glebe Place, Chelsea – I have never been happier. I sat down and waited. In spite of my confidence I was assured that I would be rejected. It couldn’t conceivably be that my book would be published by the publisher of Thackeray and the Brontës!

I returned one evening to my Chelsea basement. A letter. An acceptance from Mr. Smith. It is true that he did not offer me any money, but then he did not wish me to pay any money either.

the acceptance of his first novel by Reginald Smith of Smith, Elder & Co.

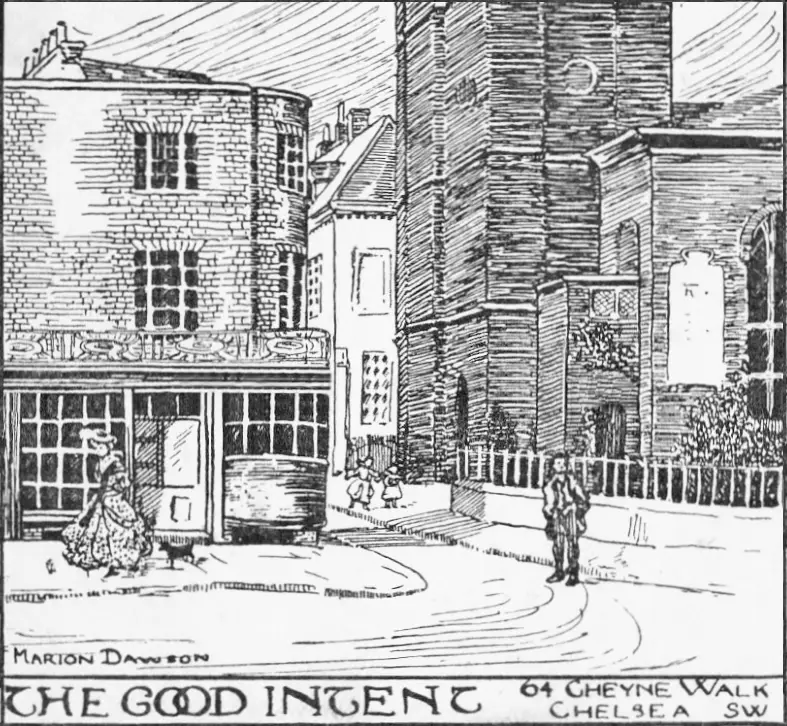

It is a platitude that never again can one know such joy as that first acceptance brings. I have known different joys since then – greater ones perhaps. But the exact taste and flavor of that first one has never been repeated. I rushed from my basement down the river, where was a small inn known as the Good Intent.

This was inhabited by artists of a sort: they sat all together in solemn assembly at one large table. I had never before dared to mingle with them. Now I rushed into their midst, told them my news, demanded that my health should be drunk. They drank it. Some of them are friends of mine yet, although the “Good Intent”, with Smith Elder and the Standard, is no more.

That young man who flourished The Wooden Horse in those artistic faces is, contrary to general information, still here.

This article first appeared in: The Colophon; A Book Collections Quarterly Part Two, published by Colophone, May 1930. Limited to two thousand subscribers.

An engaging account indeed, and thank you for rescuing it from obscurity. I only began reading Hugh quite recently, and shortly after I started to gather his books the opportunity came along to purchase 43 of them at once: most of his regularly published fiction, almost all first editions, all uniformly bound in full green Morocco by the Collectors’ Book Club of London in, I would guess, the middle 1950s. The Wooden Horse is the only volume containing an inscription: “Uncle Arthur / affectionately / from / the Author // June ’09”. It crossed my mind to wonder whether “Uncle” might possibly have been a term of endearment for Arthur Benson, but an actual Uncle Arthur seems far more likely! A pencilled price of £8. 8. 0 has been allowed to remain above the inscription, a healthy amount to pay for a treasured volume at the time the collection was being assembled.

Hi Paul, thank you for stopping by the website and leaving your message.

Wonderful you had the opportunity to purchase so many of Hugh’s works in one go – where did you discover them? What a find! The inscription in the Wooden Horse is most likely Arthur Benson since from a few years earlier from the publication of the Wooden Horse, Benson was encouraging Hugh in pursuing a literary career. He encouraged Hugh to write to Henry James which sparked the enthusiasm for Hugh to pursue the Wooden Horse, which became his first published work.

It’s well documented that Hugh was close to A.C. Benson so the term of endearment to him as ‘Uncle Arthur’ would not be surprising at all. I think that assumption is further backed up by the fact the the Walpole family tree shows that his father Somerset Walpole didn’t have any siblings. His mother Mildred Walpole (nee Barham) did have nine other siblings though as far as my research goes Hugh wasn’t close enough to any of his mother’s siblings to warrant such a dedication or presentation of his first published work. The only other Arthur in Hugh’s life was Arthur Fowler who he became firm friends with, Hugh met Arthur Fowler whilst staying with friends in 1910 (so after your book’s inscription date) to that rules him out too.

I hope you enjoy reading the books, again it’s wonderful to hear from others that discover and are interested in Walpole’s work. Keep in touch!

Best wishes

Simon

Hello Simon,

No exotic source, just an eBay listing! The seller was finding a home for the books as a kindness to a friend, the daughter of their original collector. He, or a friendly dealer, must have invested considerable time in gathering them all in those far-off pre-internet days: The Golden Scarecrow is a third impression dated a month after the first, and all the others are first printings, including six of the limited large-paper signed editions, of which four comprise the initial Herries Chronicle. All Hugh’s novels are included – Harmer John twice, as it’s in both limited and standard forms – plus the short story collections and The Waverley Pageant.

It’s a delight to me that you reinforce my guess at “Uncle” Arthur Benson, as I’ve been an enthusiastic reader of A.C.B. too in recent years, not least of his own novels which met with a very lukewarm reception in their day.

As to Hugh, I must have passed over his books many times over the years, before the Lyttelton / Hart-Davis letters induced me to obtain a copy of Mr. Perrin and Mr. Traill: not by any means the only valuable introduction that correspondence has afforded me. Making up for lost time is proceeding very agreeably. For now, thanks for your reply and for such a diligently researched and superbly presented website, which I will be exploring further: and I wish you many joys arising from the relocation to Cumbria.

Best regards,

Paul