Once again the end of the year is nearly upon us and the festive season is just around the corner. What better way to celebrate than to delve into the bookshelf and pull out another Christmas tale from the Hugh Walpole library.

This year I’ve chosen to publish one of Hugh’s short stories for children, first published in the 14th edition of Blackie’s Children’s Annual in 1917 as part of a collection of Christmas themed stories. In the latter part of 1916 Hugh was working for the Anglo-Russian bereau in Petrograd and in the midst of the first world war was already working on his longer form children’s stories to be published as “Jeremy”.

He must have found time during his busy work on war propaganda to write this short story for Blackie & Son who published their children’s annual every year, compiling work from the leading authors of the time, ready to be found neatly wrapped on Christmas morning under many a tree across the nation no doubt.

Thank you to everyone who has helped provide research and information when I’ve been compiling the posts for the website during 2022, and to all readers I wish you a merry Christmas and a very happy new year. Here’s to an exciting 2023 continuing to celebrate the wonderful talents of Hugh Walpole.

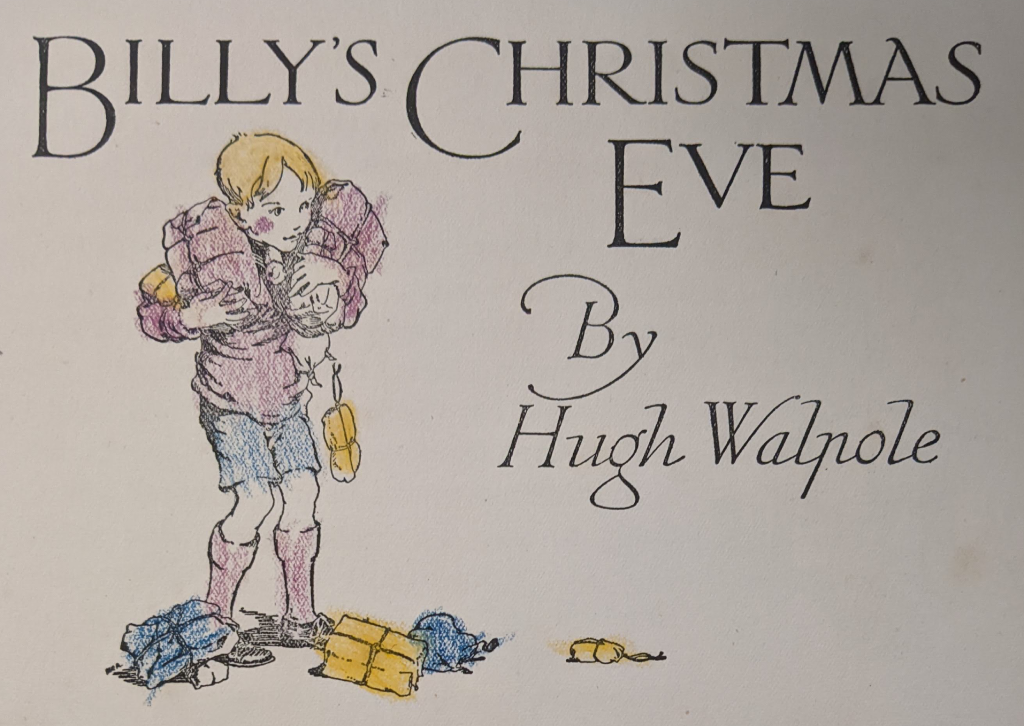

nce upon a time – and not really so very long ago there lived a boy called Billy Temple. Billy was an unfortunate boy for several reasons; one reason was that both his father and his mother died when he was very young, another reason was that he lived with his aunt, who didn’t care for him, and another reason was that he was so shy and timid that he always made the worst of himself, and his very own aunt told him that he was the ugliest, stupidest little boy in the world, which wasn’t very kind of her.

nce upon a time – and not really so very long ago there lived a boy called Billy Temple. Billy was an unfortunate boy for several reasons; one reason was that both his father and his mother died when he was very young, another reason was that he lived with his aunt, who didn’t care for him, and another reason was that he was so shy and timid that he always made the worst of himself, and his very own aunt told him that he was the ugliest, stupidest little boy in the world, which wasn’t very kind of her.

He was so deeply conscious of being ugly and stupid that he was always thinking of it, and this of course he wouldn’t have done if he had had brothers and sisters who could play with him and quarrel with him. But he wasn’t so lucky; he hadn’t got anyone.

He certainly was a plain boy. At the time of this adventure of his he was eight years old; but he was small for his age, and had freckles all over his forehead, some of them as big as halfpennies, and he had a very large mouth, and a very small nose, and large hands that were always doing the things that he told them not to do.

At the same time his aunt – Miss Emily Jones was her name – had she been a clever person – which she was not-would have perceived that he was really a very nice little boy with a kind heart, and a truthful tongue, and honest eyes-all better things to have than good looks.

However, as I say, Aunt Emily was not clever; she simply thought it a great nuisance that she should be compelled to have a little boy in her house, a silly little boy who never said anything, and jumped every time that she spoke to him. Of course she had someone to look after him.

This was a Miss West, who taught him his lessons, took him out for walks, and told him not to do any of the things that he wanted to do. I’m afraid Miss West wasn’t any more fond of him than his aunt was; she was very tall and thin, wore spectacles, and never ate meat, so that of course she was gloomy and depressed, and always believed the worst of everybody.

Aunt Emily lived in a large house in a large square in London. She was small and pretty, with golden hair and what Billy called “flowering” clothes, by which he meant that she had always roses or violets about her somewhere. But the house was gloomy and dark, with a great stone staircase, and many rooms that were always closed, with the blinds down and all the furniture wrapped up in white cloth.

Billy’s schoolroom was dull, and the windows looked on to the wall of another house. He had no pretty pictures on the walls, only a map of Europe that Miss West used to point at with a stick and ask him: “Now where’s Portugal?” and then hit him over the knuckles because he didn’t know. The house was always cold and full of strange sounds, and in the middle of the night Billy would wake up and fancy that he heard all the white shrouded furniture coming out of the shut-up rooms and walking up the stairs.

Altogether, as you can see for yourselves, Billy didn’t have a happy time. He had once, years ago, had a lovely Christmas (his own mother had been alive then).

There had been snow, and a stocking, and Father Christmas, who had given him a train with a railway; but that had been the only nice Christmas he had ever had, and the memory of it remained with him, and he thought of it all until he could almost feel the train in his hand and see the snow and Father Christmas’s beard.

Always, as Christmas drew near, he hoped that this time Father Christmas would come again, and every Christmas Eve he hung up his stocking. But nothing ever happened. Miss West was more gloomy at Christmas time than at any other time in the year, and gave him his mutton on Christmas Day as though it were wicked of him to think of eating anything at all.

Aunt Emily was out all day, and once when Billy asked Miss West what it was that Aunt Emily was doing, he was told “Bridge”. What this might mean he couldn’t imagine. He knew, of course, what a bridge was; but what Aunt Emily could want with a bridge on Christmas Day, whether she stood on it, or built it, or sailed under it, he did not know; it was only when he was older that he understood that Bridge was the name of a game of cards, just as once he had played “Beggar my Neighbour” with a friend of Miss West’s who came to tea.

The Christmas Eve of the year in which he was eight was a very beautiful one, because there was hard, glittering snow shining like diamonds on every roof, and a red sun like a round plate, and men scraping with shovels on the foot-path to clear the snow away- and that is, as everyone knows, a delightful sound to hear.

Billy, therefore, woke up in the morning and hoped that something really pleasant might be going to happen. He looked out from the window in the passage and saw boys throwing snowballs at one another, the shops on the farther side of the street bursting with turkeys and holly and toys, and a man with an organ and a monkey, and an old woman with baskets of red and yellow chrysanthemums a flower whose name he had learnt with great difficulty from Miss West. So he really hoped that something good would happen.

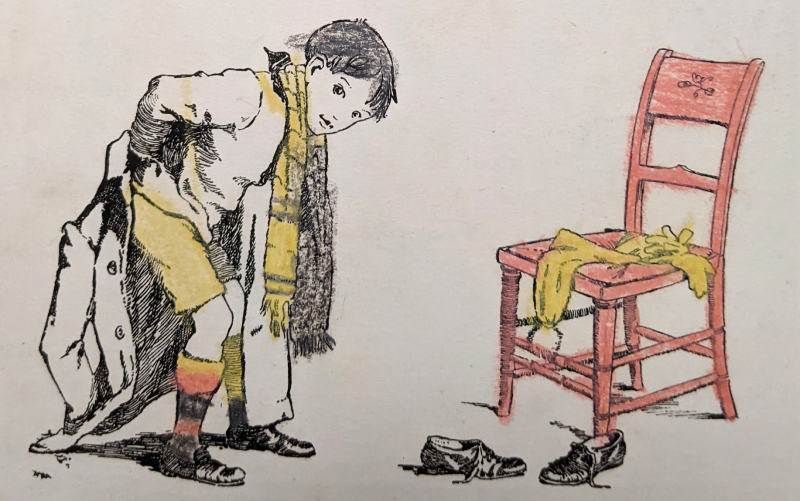

However, he was very soon disappointed. About eleven in the morning, when Miss West had just said that there wouldn’t be any more lessons to-day, because it was Christmas Eve, and Billy “wasn’t to be a nuisance now”, Jane, the servant, came in with a note. Miss West read it, and got very red in the face (which was naturally a yellow colour).

She wrote an answer, which Jane took away, and then she told Billy that he was to be a good boy, because she was going away and wouldn’t be back until tea-time, and his aunt was out for the whole day; he was just to amuse himself “by himself”, and if he wanted anything he could ask Jane or the cook down in the kitchen. Jane would give him his dinner – roast mutton and rice pudding – and he could have a second helping if he liked, because it was Christmas Eve.

Then Miss West went and put on her best hat (a very ugly one), and took her umbrella that had a parrot’s head to it, and went away, and the door closed behind her.

Billy sat up in the schoolroom all by himself and determined to be good. He got Robinson Crusoe, which he could read very slowly to himself, and tried not to think about Father Christmas, and plum- pudding (which he had never tasted, only heard of), and trains, and crackers.Then dreadful things, in spite of himself, began to happen. Have you ever sat in an empty house, in an empty room, and tried not to listen to noises? If you have, you’ll know what Billy felt.

He determined to think about nothing but Crusoe, and to hear no noises; but soon, after he had been only ten minutes alone, he seemed to hear doors opening and shutting, people coming up and down stairs, all the clocks chattering together, winds whistling, and curtains blowing. He thought of all those empty rooms with the furniture done up in white cloth, and he fancied how someone might hide there, for weeks and weeks, and no one know anything about it.

The schoolroom was very cold, the fire was nearly out, and the draught from under the door blew the map of Europe against the wall with little taps; the clock on the mantelpiece said: “Stu-pid, stu-pid, stu-pid!” over and over again.

At last he went to the door and opened it and listened. The house seemed quite silent; it was as though he was all alone in the world. He listened; then he went a little farther, and a little farther. He stood at the top of the great stone staircase, and the draught came whistling up to him from the cold hall, and the great grandfather’s clock, with the gold heads of Chinamen on it, muttered: “Come-here, come-here, come-here!”

He wouldn’t come, because the clock might do something very horrid to him if he did; but for some reason he couldn’t go back to the schoolroom, and just stood there, waiting and wondering what was going to happen next. He knew that he was very cold and very hungry; but, although he was very hungry, he did not feel as though he wanted mutton and rice pudding.

Then, as he was waiting, and shivering, and feeling as though he might sneeze at any moment, and then possibly cry, something happened, something that brought his heart hammering into his throat. The hall-door bell gave a clanging, echoing ring that came running up the stairs and seemed to hit Billy in the chest. Who could that be? He waited. Jane did not come. There was the same silence in the house as before. The bell rang again – then a third time.

At last Billy, as though he were driven by someone behind him, slipped down the stone stairs, stood outside the door in the hall, waiting; then, when the bell suddenly rang for a fourth time, turned the handle and swung back the door. He looked out. There, standing in front of him, was a large man, in a heavy black coat. This man was perhaps not very tall, but he was broad, and thick, and his face was of a dark-red colour like the dining-room table. He had a little short, black moustache, and very nice eyes, as Billy at once saw. In fact, his eyes were so pleasant that Billy smiled, without knowing that he did so.

“I’m sorry,” Billy said, “I oughtn’t to be opening the door, but Jane never came.”

“That’s all right,” said the man; “what I want to know is whether a lady called Miss Emily Jones lives here, and whether she’s in at this moment?”

“She does live here,” said Billy, “because she’s my Aunt Emily; but she’s not in.” The man looked terribly disappointed and frowned.

“Oh, but she’s expecting me!” he said; “I’ve come up especially to London to have lunch with her.”

“I’m very sorry,” said Billy politely, “but I’m sure she isn’t coming back. She’s gone to do Bridge.” At this moment Jane arrived, red in the face and rubbing her hands on her apron.

“Is Miss Jones in?” asked the man.

“No, she is not, sir,” said Jane, “nor she won’t be till six o’clock—which was her last word when she went out this morning.” Then the stranger’s face looked very black indeed, and Billy shook in his shoes. But all the man said was: “I think I’ll just write a note, if you don’t mind.”

He came into the hall as though he owned it, and Jane showed him into the little pink room that had the canaries and the smell of seed-cake in it, and handed him a pen with a blue handle and gave him some little sheets of pink note-paper. Billy, he didn’t know why, stayed close at hand. The stranger wrote his note; then he got up, and, staring at Billy as though he saw him for the first time, said:

“Do you know, it’s very selfish of your aunt. She’s forgotten me, and I’ve come a long way to see her, and I’m leaving England to-morrow.”

“I’m very sorry,” said Billy.

“She seems to have forgotten you too,” he said. “What are you doing all alone here on Christmas Eve?”

“I’m waiting for Miss West to come back.”

“And who’s Miss West?”

“Please, sir,” said Jane, “it’s Master Billy’s governess. She’s gone out. It’s lonely for the poor lamb, me and Cook being in the kitchen, and it’s a large ‘ouse.”

“Lonely! I should think it is. And on Christmas Eve, too!”

He stood there, thinking, and suddenly he wheeled round on his toes.

“Look here, he’d better come out with me! Why not? We’ve both been forgotten. I’m an old friend of your mistress’s,” he continued to Jane.

“Here’s my card. I’ll just take him off for an hour or two.”

Jane choked, as she always did when she was in trouble. “Oh, I don’t think my mistress – -!” she began.

“Nonsense!” he said (which was rude of him). “Run along, Billy, and get your things on. We’ll have an hour or two’s fun. Even if I did run off with you altogether, it doesn’t seem as though anyone here would mind very much.”

Billy ran up the stairs as though fire was behind him. This was one of those things that only happen in dreams, and in a dream he seemed to be. In a dream he put on his hat and his coat, in a dream he slipped down the stone staircase, and he dreamt he walked out of the house with the large stranger.

He had no fear, as many boys might have had, nor did it seem strange to him that this should have happened. He felt as though he had been waiting for this man all his life, and he would have trusted him with anything. One does meet people like that, sometimes.

They walked along together. It was one of those days, as I think, ideal for Christmas. There was a little brown fog, not very much, but enough to give all the lamps a mysterious haze, and to make the shops, especially the fruit-shops, like Aladdin’s cave.

The people, as they walked along, blew little clouds of smoke into the air, and all the noises, the shouts and the cries and the bells, made a kind of murmur around Billy so that he felt as though London were welcoming him, and telling him it was glad to see him.

Every kind of colour seemed to be in the air, gold and red and blue, and everyone was laughing and singing. He did not talk very much, but after a while he slipped his hand into the big warm glove of the man, and, with a boldness that surprised himself, he said:

“What shall I call you, do you think?”

“I think Uncle Roger would about suit it,” said his friend. Then they began to talk, just as one talks in a dream, confessing many things that, in real life, one would never confess. For in- stance, Uncle Roger admitted that, although he had been all over the world, and had seen natives with rings in their noses, and snakes as thick as your arm, he could not bear beetles, and Billy confessed that he sometimes cried at night when the wind hissed, like a serpent, through the wall-paper, that he hated Miss West and arithmetic, and that he did not like having his face soaped, even now when he was eight years old.

Uncle Roger told him that he had not been in England for a long time, and that he had come back this time especially to see Aunt Emily, and that it was very sad that Aunt Emily had forgotten all about him. However, they decided then that they, in their turn, would forget all about Aunt Emily.

The walk became more and more wonderful. They came to the bottom of a hill, and at the top of the hill was a great church, all dark and shining in the smoke and fog, with a round golden dome – and this church, Billy understood, was called St. Paul’s.

The hill was thick with people, carts were pushing their way, men were shouting, and the great church bells were ringing. By the side of the pavement stood men with little things in trays that they were selling. Billy’s eyes glistened. He had never seen such things and they cost only a penny apiece. “Which will you like?” said Uncle Roger. “This one-no. I think, this-oh! if you don’t mind, this one.”

How was he ever to make up his mind? “I tell you what we’ll do,” said Uncle Roger; “we’ll buy one of each.”

So he did. There was a snake that came out of a shell, a tiny clock that rang a bell, a little doll in a red cotton shirt, two soldiers who fought one another when you pulled a string, a gold pencil, a monkey that ran up and down a stick, a little green book with dates in it, a red and white bead necklace, a pair of bootlaces. All these things Billy had, tied up in little parcels of thin red and green paper. He sighed with happiness.

“Now we’ll go and get something to eat,” said Uncle Roger.

Under the very dome of the great church they found a little quiet street with low dark shops in it, and so quiet that you could not believe that only a minute away everyone was making such a noise. Here Uncle Roger pushed back a door and went inside, and Billy followed him. They were in a room with a black roof and black walls, and on these walls hung shining brass plates.

The room was divided up with wooden partitions, and behind each partition was a table with a white cloth and knives and forks. At one of these they sat down, and then Billy had the proudest moment of his life. He was here sitting at dinner with a large grown-up man, and another man came and asked him what he would like to eat, quite gravely, without even a wink.

“I think,” said Uncle Roger quietly, “we’ll have turkey and sausage and mashed potato, and afterwards plum-pudding, and then oranges and almonds and raisins.”

There was a wonderful sentence for Billy to hear, when he should by right be attacking mutton and rice pudding in the schoolroom. “Turkey, sausage, plum-pudding, oranges, almonds, and raisins!” His throat choked, although he was not really a greedy little boy.

Then it all happened. The turkey melted in his mouth, the sausage was so fat that it burst its skin, and he was allowed to put a lump of sugar in his orange and suck it, and at the end a whole box of dates appeared, those golden, sticky dates, with hard, clean stones inside them, and a stick running through the middle of them. Meanwhile there was sand on the floor, and gentlemen came in and ordered things in loud, hearty voices, and no one thought it odd that Billy, who was only eight, should be sitting down with them.

At last they were in the street again, Billy holding tightly all his little red and green parcels.

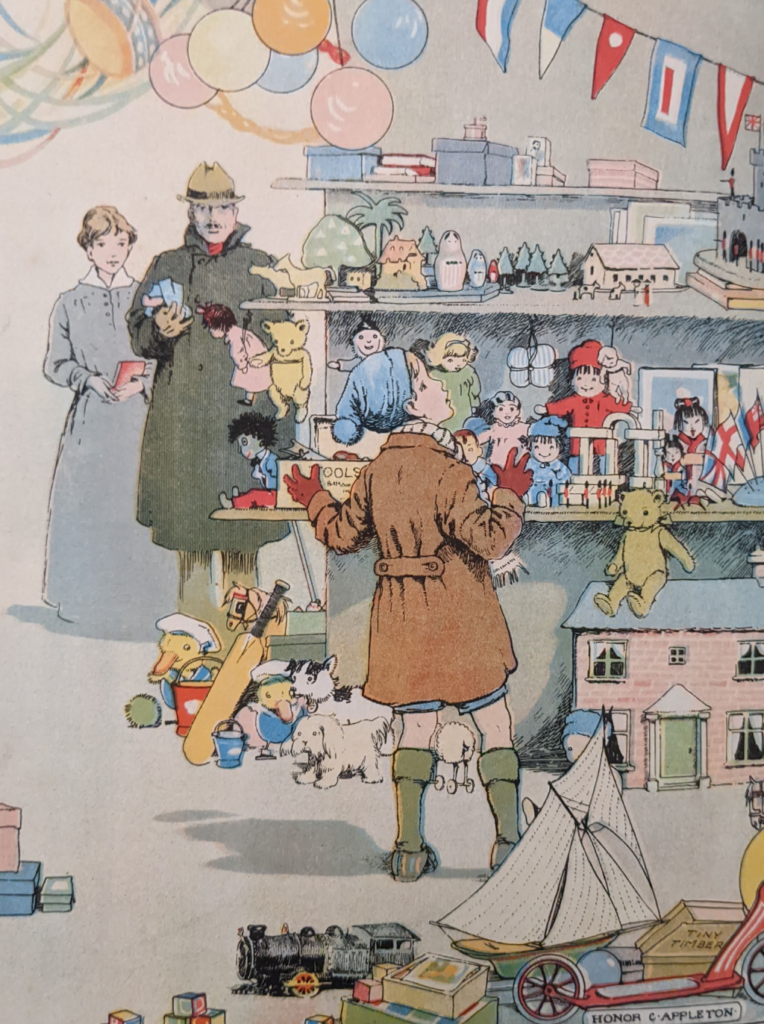

“Now,” said Uncle Roger, “you come along with me.” They walked down the hill, turned up to the right, and were soon walking into a shop that was so large that it seemed to have no end to it, and was so shining with lights that it was a long time before Billy could see what was there. When he did see he cried out aloud. It was all nothing but toys – toys large, and toys small, animals and dolls and trains and soldiers, and fish swimming in water, and carriages, and towns built of bricks, and guns and doll’s- houses, and pictures and coloured balloons, and masks and whips and reins, and monkeys, and puzzles and rocking-horses and suits of armour.

“Now,” said Uncle Roger, “you choose whatever you like best in this place.” What a thing to say to a boy! Could anyone ever choose? How could one, without losing one’s head altogether? And Billy, mind you, who had never had toys, who was never given presents!

What a situation!

I can’t go on with this story forever, so I leave you to imagine how he walked up and down like a mad boy for hours and hours (or so it seemed to him). First he thought he’d take soldiers riding on horses and carrying golden swords, then he thought he’d have coloured bricks with which you could build a castle to the ceiling, then he thought he’d have a horse with real hair and red leather reins, then a box with tools, so that you could make a table, then a fort with white tents and cannon. He could not tell. How could he ever choose? He wandered about, his face red, his hands rising and falling, his eyes shining.

At last in despair he said: “There’s the castle with the soldiers in it, and the things for making

tables and chairs. You choose, Uncle Roger.” “You shall have them both,” said Uncle Roger.

After this they came out of the shop, and a cab was called (there were very few motor-cars then). They got inside; all the parcels were put on one side of the cab and Uncle Roger and Billy sat on the other.

Then Billy suddenly thought that nothing really mattered except Uncle Roger. The streets were lovely, the dinner was lovely, the presents were lovely, but only Uncle Roger really mattered. He flung his arms round him and kissed him, and Uncle Roger held him close with his strong arm about him and kept him like that until he was nearly home.

“I don’t want to go back,” said Billy. “Take me with you. I’ll be very good and do everything you tell me.”

“I’m coming back,” said Uncle Roger, “a year from now. What do you say to coming and living with me then? Can you be patient until then?”

“Yes, I’ll be patient,” said Billy.

Now the interesting part of this story, which is a true one, is that Uncle Roger really did come back, and Billy really did go to live with him. And, if you want to know the whole truth, he is living with him now, and is as happy as the day is long.

He has still got the monkey on a stick that Uncle Roger bought for him in the street, and he keeps it with him to remind him of the happiest Christmas Eve any boy ever had.

– Hugh Walpole.