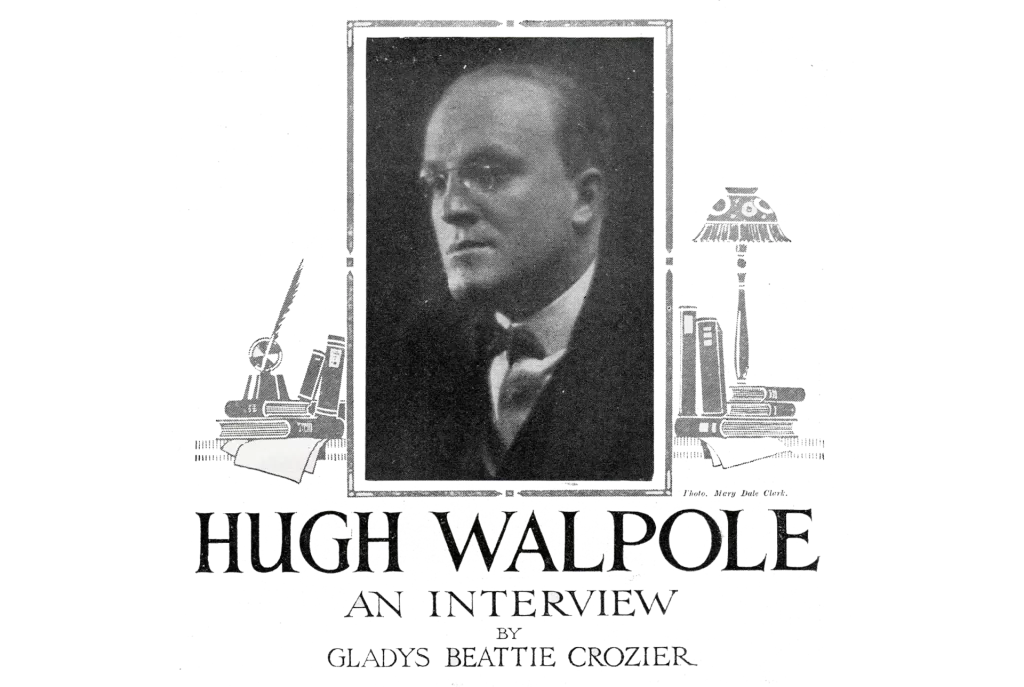

In early 1924 Hugh Walpole was living in London at 24 York Terrace, overlooking Regents Park. By this time he had become the successful author he had always dreamt of being, having at that time both the fame and the wealth that went with it. Around the same time he had discovered and purchased a new home in the Lake District – Brackenburn, his “little paradise on Catbells” and eventually also leased a flat at Piccadilly, eventually relinquishing York Terrace.

The popular press of the day were keen to interview Walpole, and one of the most prominent literary magazines of the time, George Newne’s The Strand, decided to do an in depth study of Hugh’s rise to fame. Here it is in its entirety.

With Mr. Hugh Walpole as with so many other men of literary genius, his love of books and eagerness for story-telling showed itself early. Directly he could read he started to devour every tale he could lay hands on. Almost all his pocket money went on books, and, as a very little lad, the gift of a complete set of the Waverley Novels gave him the keenest pleasure.

His gift for story-telling first came to light at school, where he was on one occasion discovered relating some specially thrilling tale, “made up out of his head,” to a fascinated audience of eager little boys in the dormitory at two a.m. ! At home, during the holidays, his younger brother and sister were constantly regaled by some absorbing history of adventure, and he also wrote long stories constantly. Several of these are still preserved in some numbers of a “Christmas Miscellany” chiefly written by himself, containing long and short stories, poems, and articles, two in one number being on such ambitious subjects as “The Literary Aspect of 1902” and “The Glories of Literature ” !

The elder son of the present Bishop of Edinburgh, and a descendant of Horace Walpole, Mr. Hugh Walpole was born some thirty-eight years ago in New Zealand, and, although he and his parents left soon after he was three years old, he still has a vivid recollection of his father coming down to breakfast one morning in a state of considerable agitation, news having just reached him that a volcanic mountain near their home was in a state of active eruption, and that the famous Pink Terraces, a well known landmark of lava construction, had just been totally destroyed.

Educated at King’s School, Canterbury, and Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he took History – after one or two “orientations” to see in which quarter of the compass his real talent lay for making a name – he came up to London at the age of twenty-three with the manuscript of a novel in his bag, and, as he says, “precious little else,” determined to carve out a career. Mr. Walpole was certainly born with a good firm grip on the illusive skirts of “happy chance,” upon which, despite various sharp knocks and buffets, he has always managed to keep hold, for whenever in his early days he was just about down and out something always turned up.

His story of his first chance is enthralling. “Ensconcing myself in cheap lodgings in Chelsea, I prepared to look round for suitable work. I had just one London acquaintance likely to be of use the late S. H. Jeyes, sub-editor of the Standard, whom I had met the summer before, at tea, down in Cornwall. He had asked me to call should I happen to be in town, so I wrote, and received a prompt reply to see him. After a desultory chat, mostly on books, he invited me to a literary luncheon party, which proved to be the starting-point of my career.

During the luncheon someone mentioned a new novel and asked the name of the author and publisher, which, by luck, no one but myself knew. From this the talk turned on modern fiction-a subject on which I was particularly keen. I talked, I remember, for all I was worth, hoping to impress Jeyes – with unexpectedly successful results, for, drawing me aside as the other guests were taking their departure, he told me that the regular fiction reviewer for the Standard had fallen ill, and asked if I would care to try my hand at reviewing a few novels. I jumped at the suggestion, and carried off an armful of new books to my lodgings at Chelsea. Setting to work after infinite pains I got the reviews done and, reading them over, decided that they were very bad.

Quite in despair, for I had done my best, I stuffed them into my pocket and wandered down to the British Museum Reading Room – a favourite haunt – where the first person I ran into chanced to be a woman friend who I knew also did a little writing. In my extremity I urged her to come and have tea in the gloomy Museum Tea Room, while I inflicted my reviews upon her for her criticism and advice. She listened patiently, and when I had done said gravely “Yes, they are awful!” at which confirmation of my fears I was terribly distressed.

She said what she could to comfort me, following up with some excellent advice: “Go home, take a nap, then light a cigarette and sit over the fire and re-write your reviews quite naturally – as though you were describing some books you’ve just read to a friend. I did so, re-wrote the reviews, which were accepted, and another batch of novels sent, and it finally ended in my being given the post of regular fiction reviewer to the Standard at a fixed yearly salary. This post I kept for four years, writing novels in my spare time, until my income justified my giving up a form of work which is, I think, very bad for a novelist.

I would advise all new recruits to cut reviewing as soon as they possibly can. Naturally, a novelist has every right to review a brother writer’s novel, provided he signs his name, thus making it clear that he is merely expressing his own individual opinion. A novelist is likely to have far too many prejudices to make an unbiased critic of fiction, and this makes it rather unfair for him to write unsigned reviews.

I think, continued Mr. Walpole, that writers should pay as little attention as they possibly can to praise or blame. If they are going to be any use at all they must follow their own individual course, and, though they should listen to what people say, they should never alter their course because of adverse criticism, or let praise turn their heads.

Once, I remember, in in my very early days, a wise old lady who had chanced to find me puzzling over a batch of contradictory reviews shrewdly remarked: ‘Don’t worry! Your book is certainly not so good as those who praise it say, and probably not so bad as those who blame it say!’ – a piece of bracing consolation in which that word ‘probably’ struck rather coldly, I remember, on my ear.

Novelists, continued Mr. Walpole, and perhaps all readers of fiction, get to like one special type of novel, to the exclusion of all other kinds – but there isn’t one perfect type of novel. At the moment critics are inclined to praise exclusively the very realistic novel, but the purely romantic novel has had a wonderful day in the past – indeed, until quite lately and will certainly have a wonderful day again, most probably in the near future.

A bad psychological story is so much worse than a bad adventure story – really there’s nothing so awful! The only thing that matters is that a novel should be good of its kind.

When did I first start writing? Why, I’ve always scribbled from the time that I could read, though most people thought it a great waste of my time. I suppose that my actual working hours are about three hours daily, but, of course, I am thinking out the book I have on hand most of the other time. I like to get it all clearly thought out in my head before I start to write it down.

In the last dozen years or so, despite the long interruption which the war entailed, Mr. Hugh Walpole has managed to get through an amazing amount of work, for more than a dozen novels and romances, including “Mr. Perrin and Mr. Traill, “Fortitude,” “The Duchess of Wrexe,” “The Prelude to Adventure,” together with “Jeremy,” “The Green Mirror,” The Cathedral,” and those two remarkable stories of Russian life, “The Dark Forest” and “The Secret City,” stand to his credit, besides a most interesting monograph on Joseph Conrad, for whose work he has an immense admiration, and innumerable articles and short stories, written for the magazines and reviews, both here and in America.

Which do you consider your best piece of work? I inquired. I think, on the whole, The Green Mirror, and that, too, is my favourite book, replied Mr. Walpole, though the character of Maggie in The Captives is my favourite individual character, and the one on which I have expended the greatest thought and care.

No, my characters are nowadays drawn solely from my imagination. Only once have I drawn people from those I have met. It was in my early days, when I was very young, and I regret doing it. It’s bad art and bad manners, declared Mr. Walpole, emphatically. You make an exception of Jeremy of course? I asked. I must admit that much of that is autobiography, he confessed, cheerfully.

Apropos of his very successful lecturing tours in America, Mr. Walpole tells several amusing stories. At the very beginning of one of my tours I travelled a long distance to a rather out-of-the-way spot to give the second lecture on my list at an American Social Club. On arrival on the platform, feeling rather nervous, for I had done little lecturing before, the chairman, a local minister, opened the proceedings by making a short speech, exhorting the members present to subscribe generously to the new session and leave no stone unturned to collect the funds upon which the success of the forth coming lecture season must depend, winding up his exhortation with the remark: “If we had only had more money we could have had an even better lecturer than we have here to-night!” as he turned to introduce me to my audience !

On another occasion an amusing incident occurred at a small town in the neighbourhood of San Francisco, when, after a three days’ journey, Mr. Hugh Walpole, very brisk and smiling, and well prepared for the usual reception committee of women, who would, he knew, in accordance with the usual hospitable plan, be drawn up on the platform to greet him, prepared to step out of the train.

Just as he was about to alight, a cadaverous-looking old man – by no means clean, with bent shoulders, and a thatch of untidy white hair clinging in wisps about his ears-stumbled out of the train before him and almost into the arms of the assembled ladies, who welcomed him with the keenest enthusiasm.

His urgent refutations regarding his supposed identity were received with brisk disbelief. Not Mr. Walpole? You must be Mr. Walpole! he heard the leader firmly remark, and decided it was time to step forward and introduce himself-only to be met with an unbelieving stare, while the spokeswoman of the deputation, clearly voicing the general opinion, remarked with scorn: You? You never wrote those books!”

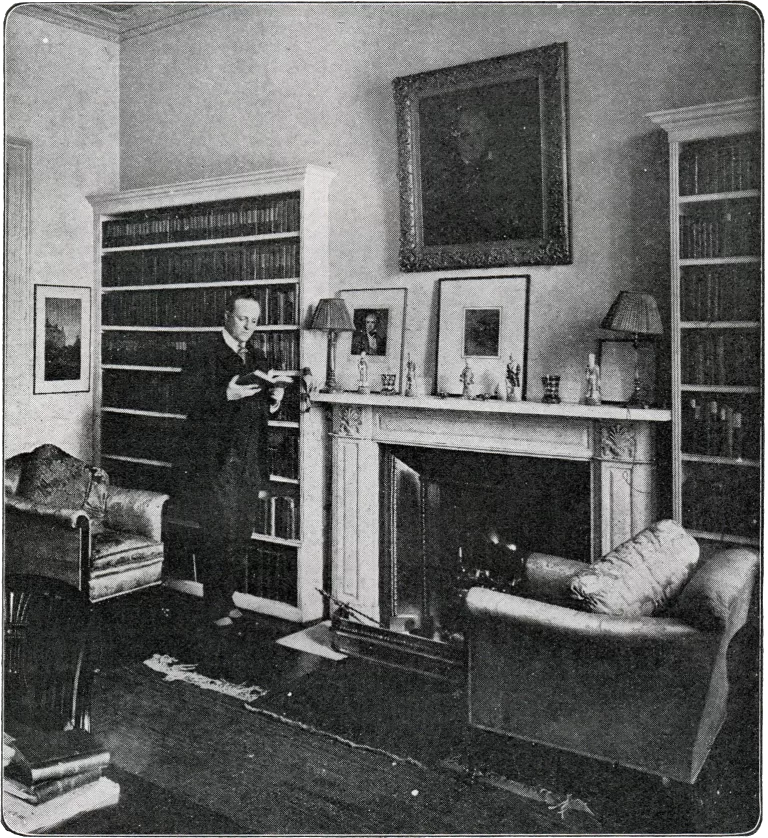

When I met Mr. Hugh Walpole, he was living in a house in York Terrace, overlooking Regent’s Park. It had a homelike look, with its big jars of flowers, a blazing fire, flanked by great saddle-bagged arm chairs, and a charmingly-appointed tea table; his library was a most cheery and supremely comfortable setting for a chat on a cold winter day.

There is much originality in the decorations, which strike a pleasing and somewhat Russian note, with their emphasis on harmoniously-blended shades of deep blue and red, in the woven rugs which adorn the black-painted floor; curtains of deep Russian blue brocade make a gorgeous splash of colour, and lamp-shades and cushions are of shot red and blue silk. The ceiling is painted a very bright vivid blue.

The whole wall space is covered by tall, ivory-painted bookshelves, which completely surround the room and stand eight or ten feet high.

The centre of the library is occupied by Mr. Walpole’s huge writing table, adorned with a quantity of signed and framed photographs, amongst which a couple of good portraits of Joseph Conrad, one of Arnold Bennett, and one of Chaliapine catch the eye.

Here Mr. Walpole keeps his specially rare books – two volumes of the first edition of “Robinson Crusoe,” a specially fine first edition of Keats’s “Endymion,” and Charlotte Brontë’s first story – written when a child in minute characters on dolls note paper-enclosed in a wee leather case. Also, the Italian grammar used by her as a girl, which bears her name upon the flyleaf.

An autograph copy of Guinevere given by William Morris to Burne-Jones, with a note in the poet’s handwriting upon the title-page, is another special treasure.

Mr. Walpole is an immense admirer of Sir Walter Scott. He devoured all the Waverly Novels directly he could read – his favourite is still “Red Gauntlet” and his enthusiasm and affection for the great writer remain unbounded. Sir Walter’s life-sized portrait in oils strikes a dominant note over the library mantelpiece, flanked by a tall bookcase devoted to first editions of all Scott’s works, and of every book of note written concerning him.

The portrait was painted by McFie after Raeburn, and a fine mezzotint of the Raeburn portrait stands on the mantel piece, beside a coloured crayon drawing by Sir David Wilkie, which shows Scott in his later days. wearing a night-cap, with a plaid wrapped round his shoulders, sitting propped up in a high-backed easy-chair.

Other relics and souvenirs are scattered about the room; the embroidered wool work slippers worn by Sir Walter up to the time of his death are enshrined in a glass case, while his death-mask, cast in bronze, lies on the writing-table. By a most fortunate coincidence, Mr. Walpole, when in San Francisco during one of his recent lecturing tours, chancing to roam into an old bookshop, ran across seventy unknown and unpublished letters of Sir Walter Scott’s, written by him to his solicitor at the time of his financial smash. He learnt that they had been brought in by the grandson or granddaughter of the solicitor a day or two before and promptly bought them. Now, mounted in a magnificently bound red morocco book, each one in a separate page, with a carefully transcribed type written copy opposite, they form the greatest treasure in the library.

None of the letters has been written about or seen, and it is with special pleasure that I obtained permission to copy one of the most interesting of the shorter letters for the readers of The Strand Magazine.

Written just after the crash, it runs as follows:

My dear sir,

I have this morning the very unpleasant news that Constable’s house must stop payment, by which I will be greatly embarrassed

At the same time, I have so many hypothecs upon my works done and to be done, that I hope I may work through without great ultimate loss.

Mr. Hogarth, who manages the matters of Ballantyne and Co. and knows the whole affairs personally, will explain them to you.

Yours truly,

WALTER SCOTT.

Abbotsford,

Tues. 17th January, 1826.

Glancing at random through this most fascinating volume one is struck by the picturesque felicity of phrase which runs through even his business correspondence, as, for instance, in the letter to his solicitor’s partner, whom he has lately recommended to the Duke of Buccleuch as business agent for some of his affairs. “A thread delicately handled has been the means of pulling up a cable,” remarks Sir Walter, shrewdly, going on to add: And I would fain think that this partial but confidential employment may lead to something better here-after.”

All my serious book-collecting has been done during the last seven years,” remarked Mr. Walpole, “and I am also collecting autograph letters of famous literary men and women – Robert Browning. FitzGerald, Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, Trollope, Dr. Johnson, and Charles Lamb are amongst them.

A very special feature of Mr. Walpole’s library is his collection of the great novelists, many first editions and in the original bindings, which range from John Bunyan (not a first edition!) to Joseph Conrad, Thomas Hardy, and Rudyard Kipling. It fills the entire side of one long wall. Most of the volumes are extremely rare, and the whole forms a most compact and probably unique collection, and an invaluable reference library on a subject on which Mr. Walpole is so often asked to lecture – English fiction.

Here one notices a shelf and a half devoted to Thackeray, a long row of George Eliot – including “Daniel Deronda” in the first paper-covered edition – Meredith, Whyte-Melville, Kingsley, and half of George Gissing – including “The Unclassed” and “New Grub Street.”

There is a specially fine collection of Anthony Trollope, including “Can You Forgive Her?” and “The Last Chronicle of Barset,” and one must not overlook those two delightful books of humour,” Works,” by Max Beerbohm, and “The Trials of the Bantocks,” by G. S. Street

I take a great interest in trials, said Mr. Walpole, cheerfully, pointing out another bookcase in which a couple of shelves are devoted to various chronicles of crime and learned dissections of the motives which inspired them, which must always have a special fascination for the student of human nature. “The Trial of the Seddons” and “Crippen,” edited by Filson Young; “The Trial of Eugene Aram,” by E. R. Watson, and a whole edition of “Notable Scottish Trials” included, while on another shelf I noted a couple of beautifully bound volumes with the gruesome title. “The Confessions of a Thug “!

Another shelf is devoted to books on the Great War, while just below is a magnificent edition of Horace Walpole’s Letters bound in brown leather. A whole bookcase is devoted to modern French, Scandinavian, Russian, and Italian writers.

On the right-hand side of the fireplace are rows of shelves devoted to the poets. Here again the same catholic taste prevails in the wide choice, which ranges from plays by Ben Jonson and the poems of Keats, Browning, and Swinburne, and “The Ingoldsby Legends,” to slim volumes of verse by Walter De La Mare and plays and poems by John Drinkwater.

Mr. Walpole’s account of his first meeting, at the outset of his career, with Thomas Hardy is amusing. A friend of mine who knew the Hardys well, he said, offered to take me there to tea. I accepted the invitation with alacrity, and on arrival was duly introduced to the great man and the late Mrs. Hardy – his first wife – who, entering into conversation with my sponsor, left me and Thomas Hardy to sit and gaze at one another. This we proceeded to do, my host not apparently thinking any attempt at conversation necessary.

At last, goaded into speech by the pro longed silence, I blurted out a remark upon the fineness of the weather. Mr. Hardy concurred in monosyllables, and silence reigned once more – broken presently by Mr. Hardy, who, rousing himself and asking my plans, learnt that I wanted to become a writer.

What kind of books do you propose to write? he asked. I hope to write novels, I replied. Don’t! advised Thomas Hardy, laconically, before relapsing once more into silence!