With the sad passing of Queen Elizabeth II this week I looked through my Hugh Walpole collection to see how I could prepare an appropriate article of tribute. Of course Hugh Walpole died 11 years before Elizabeth was crowned as Queen, however in 1936, as Princess Elizabeth of York and at the age of just 10 years old, she was involved in the preparation of The Princess Elizabeth Gift Book.

The book was to be published as an instrument to raise funds for the Princess Elizabeth of York Hospital for Children in East London and featured a compilation of short stories from the leading authors of the time including amongst others, J.M. Barrie, G.K. Chesterton, Compton Mackenzie and indeed Hugh Walpole. Whilst most of us know Elizabeth of course devoted herself to the duty of her country when she became it’s ruler in 1952, clearly even at such a young age she wanted to play a part in helping others.

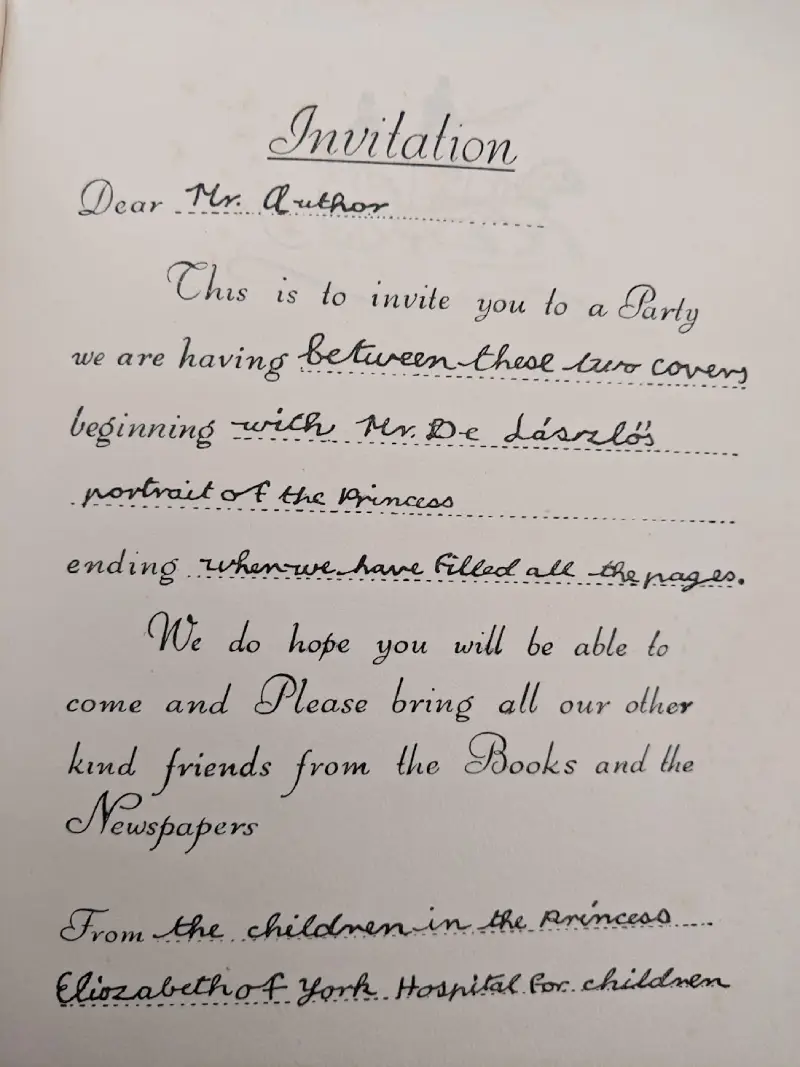

The book commences with an invitation from the children in the hospital to the authors inviting them to a ‘party between these two covers’. Hugh Walpole of course obliged with the contribution of a short story titled “The Chair With The Gold Thread”, a story about a child who lived within a regime of rigid rules and a household of continuity and history and a connection with a regal chair.

Quite apt for a book written with a royal subject as its instigator, although of course Elizabeth was never originally destined to be in direct line to the throne. I wonder if it was because of the then impending potential abdication of Elizabeth’s uncle at the time, that the ‘thread’ of the story so to speak, seems to give prominent nods to how the then princess’ life could be about to pan out – would she or wouldn’t she be destined to be a future queen?

The story is published in full below in tribute to the passing of Queen Elizabeth and as eerily as ever with Hugh’s writing pay attention in particular to the very last line of his story – it very much seems to befit the present mourning by the country some 87 years after being written.

We now in turn revert to, as Hugh would have done in his times too, the exclamation:

God Save The King!

The Chair With The Gold Thread

By Hugh Walpole

Once upon a time when I was very young, we lived in a house which had, as I then thought, the most beautiful room in the world. I expect if I saw it now I would think it overcrowded with things, for in those days, forty years ago, people still lived in rooms filled with little tables and many chairs.

On the tables there were photographs and little mats and large books with leather bindings. There were so many things here that everything had to be arranged exactly in the right place, because if it was out of order at all it interfered with other things, and it was very difficult not to knock something over. We had our own schoolroom in which we could play about as we wished, and this was a very empty place with a large table, a doll’s house and a rocking-horse without a tail.

Children in those days did not go into the rooms where their elders lived, except on special occasions, and into the drawing room this lovely place of which I was just now speaking – we only went as a very special favour: if, for instance, some visitor had asked to see “the dear children,” or if one of us had a birthday. The facts that these visits were so rare gave an added charm to these occasions.

I remember that room as though I had been into it only yesterday. I can see the lovely curtains, that were of some deep purple colour; the pictures on the walls, one especially called “Christ leaving the Prætorium,” and another of a number of children dancing round Father Christmas; then over the mantelpiece there were portraits of a lady and a gentleman in very old-fashioned clothes. They were in colour, and the gentleman was especially attractive because he was in military uniform and wore a sword.

I was told he was my great-grandfather. There were a number of tables, all covered with little things, and, most fascinating of all, there was a case with a glass top, and in this case little gold and silver boxes and some red and green seals, and a chain of ruby-coloured stones. On another table was a set of red and white ivory chessmen, and there was a big musical box with a painted lid of shepherds and shepherdesses.

On the mantelpiece were two large Chinese figures that nodded their heads if you touched them, and a big gold clock with the moon and the stars painted above the dial. The things that especially fascinated me were some large fans fastened on to the wall.

This room had a settled air about it, as though all the things in it had been there from the beginning of time, just exactly there in those same positions. What charmed me then I should not like now, namely, that there was very little human life here.

I liked it then, I felt that it was right and proper for the things to be more important than the people. I can see my grandmother now, sitting in a large arm-chair near the fire-place, with her lace cap and white mittens, and a big coral brooch resting on her black silk dress. She is connected for ever with that room in my mind, and I cannot see it without thinking of her.

But for myself the most irresistible attraction there was a small chair. This chair had back and arms and feet of gold. The seat was covered with glittering gold thread. It was set apart by itself near the big windows that looked into the garden. I heard that it was very, very old and one of the most valuable things that my grandmother possessed.

In my own mind it looked very much more splendid than anything else there, and, in fact, it was the most handsome thing that I had ever seen. Its lines were so delicate, its curved back so gracious, and it was so sure of its own splendid position. I was told again and again that never, never must I touch it, and I received the impression that if anybody did touch it, it would at once fall to pieces.

But of course this very order that I was not to go near it made me long to stroke it, and on those important occasions when I was summoned into the drawing room, I would look at the little gold chair with all my eyes as though I had some personal relationship with it.

Children were very sternly brought up in those days, and when one was told not to do something the penalties that followed disobedience were truly terrible, not so much the punishments themselves but the sense of dreadful disgrace, of being thrown out from all the world of proper behaviour – and perhaps most awful thought of all – never getting back into it again.

I had at that time a governess, whom I will call Miss Clay. She did not like me, and of course I did not like her. Now, looking back, I am sure that I was a most tiresome, difficult little boy. Tears flowed very readily, and I had a great sense of the dramatic as regards myself.

When I was punished, it seemed to me that the whole world was concerned, and I took my pleasures so seriously that I was never light-hearted and at ease, even when I got what I wanted. I was also, I think, a great coward, but at the same time something in me made me long to do what I was forbidden, and if I did wrong I always blamed other people for it. And yet nobody ever wanted everything to go right more than I did, and I never could understand why things were so continually going wrong.

In any case I hated to do what Miss Clay told me and she, irritated, I suppose, by all my naughtiness, was continually ordering me to do things she knew I disliked. In the old days it was considered good for children to do what they disliked. Now perhaps things have gone a little too far in the other direction.

Two things above all I was told not to do: one, to go into the drawing-room without permission, and secondly, to touch the little gold chair. Both things I longed to do. In fact after a while the little chair, I think, began to haunt me. I dreamt about it at night. I used to fancy that it wanted me to go into the room and sit on it, and that it would rather I sat on it than anybody else in the world. From that I began to feel that it belonged to me, that it had been stolen from me, and I invented wonderful stories about wicked people taking it from me, and that it never would be happy until it came back to me again.

So there followed one of the most awful events of my life. Now, indeed, after all these years I am inclined to shiver if I picture for a moment to myself the dreadful scene. It all happened very quickly and was over very soon, as is the case so often with the most important things in life.

One winter afternoon, when the snow was falling too heavily for me to have my usual walk, and the house was muffled in a kind of white silence, when Miss Clay had fallen asleep in her chair, an open book on her lap, I suddenly yielded to temptation. I stole out on to the landing, listened to hear if anybody was about, crept downstairs (and I remember how exactly it seemed that my heart really was in my mouth, filling my throat with a noisy beating). Outside the drawing-room door I paused again. If at that moment there had been a sound anywhere, I would not have gone forward, but the silence of the house and the sense of the snow falling so steadily drove me on.

I opened the drawing-room door and entered it, for the first time in my life, without permission. I stood there in the room, watching the fire leaping in the fire-place, all the silver shining and the garden beyond the windows white and soft under the grey, cold sky. Then I went forward. I pulled my grandmother’s arm-chair towards the fire-place, climbed on to it and set the heads of the Chinese figures nodding.

This I had for years longed to do. Then I climbed down again and went very softly to the little gold chair. I stroked its back and its arms and then, with my head up as though I were challenging the world, sat down upon it. What a triumph for a moment I felt! It was as though I owned the whole world – at any rate, I owned the drawing-room and everything in it, and I felt part of the little chair, as though we belonged to one another, and would never separate again. I was happy and terrified at the same time.

In very fact my terror had reason. A moment later the door opened and there stood my grandmother, leaning a little on her ivory stick and with her some half-dozen visitors. “I am so glad you’ve come,” I heard my grandmother say. “We will have the lamps lit, although it’s so early.”

She moved forward, not seeing me at first, and I was transfixed there and unable to move. Then she saw me, and gave a little cry. I jumped up and as I did so I heard a dreadful tearing sound. My quick movements, the roughness of my sailor trousers, tore many of the old thick gold threads of the seat of the chair.

I stood there, looking at my grandmother; my grandmother, who was one of the gentlest of God’s creatures, lost for a moment her control, raised her stick, and I thought that she was going to strike me. However, all that happened was that she turned to her guests and said that this was her little grandson, Hugh. I shook hands with them, and the two ladies kissed me and I left the room.

Punishment was later. I was sent to bed without supper. Miss Clay treated me as though I were one of the lowest of the criminal classes. My grandmother herself never said another word, but for weeks I moved in a dreadful thick, never-shifting cloud.

My grand mother’s distress was bad enough, but what was worse was that the little gold chair was removed. In fact I never saw it again. From that awful afternoon until this day I have never seen it.

So I lost something for ever, and I like to think that the little gold chair on its side lost something, too.

Hi, nice to see info about this interesting book. What caught my eye were two Disney illustrations forward and aft in the book. They are unique and, I think, inked exclusively for this book. They are spectacular and can be easily removed for framing without damaging the book, aside from their obvious questionable removal.

Hi Richard

Thank you for your nice feedback about the post, I’m glad you found it enjoyable. Indeed those two Disney illustrations are spectacular and would be lovely to frame up. I’d advocate scanning them and making a re-print rather than taking them directly out of the book, though that’s of course just my preference in keeping my library items intact – each to his own!

Take care and thanks again for the comment!

Best wishes

Simon