Since it’s nearly Halloween what better time to celebrate the darker side of Hugh Walpole’s writing.

Reading some of the many macabre books and short stories he wrote, you’d be taken to thinking that perhaps at times Hugh might have been bordering on being a crazed psychopath, he could certainly send a chill up your spine with some of his works.

Though dig deeper and you’ll find intelligent, thought provoking and extraordinary glimpses of torment and insight in the inner workings of the human mind.

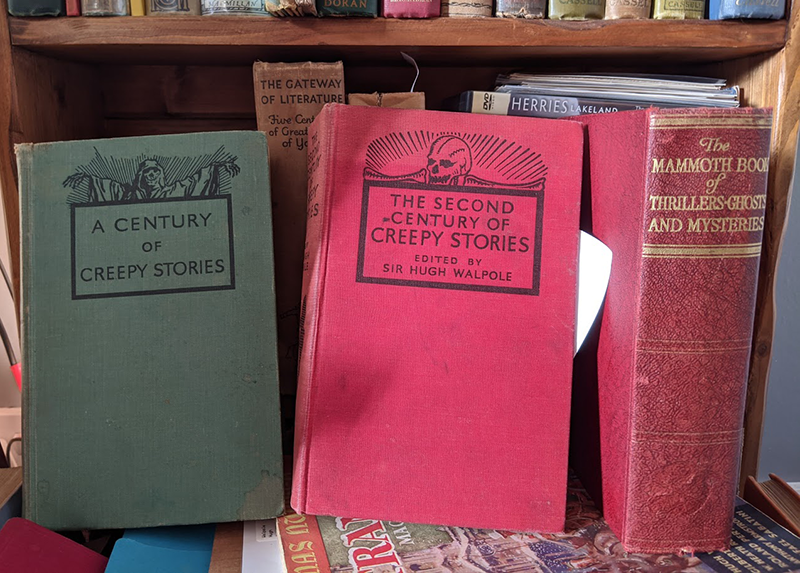

Two short story compilations from the 1930s that feature Hugh’s scary stories among works from other writers are a good example I’ve chosen from my library.

They were aptly named “A Century Of Creepy Stories” and “The Second Century Of Creepy Stories”, the latter volume which Hugh himself edited.

I’ve selected a short story from the first volume called “The Tarn”. Originally written in 1923, it’s a good example of Hugh Walpole exploring duality of the human experience and what mental torment can drive a person to become.

Perhaps Hugh was drawing on his own demons, even using the page as a therapy to explore and expurgate them.

Through the centuries, the most successful creatives have always had the ability to harness the power that emanates from the friction between the conflict of darkness and light, sanity and insanity, the good and the evil, and Hugh Walpole certainly knew how to spin a scary yarn or two.

Carve yourself a pumpkin, light a candle, turn down the lights and read on.

Happy Halloween!

THE TARN

by

Hugh Walpole

Audiobook

A short story of two friends with quite different temperaments, in which one hates the other, though keeps it very well hidden.

The story ends badly for both though it is how the final death happens which makes this a suitably weird tale.

Reading & Production by David Wales

Text Version

As Foster moved unconsciously across the room, bent towards the bookcase, and stood leaning forward a little, choosing now one book, now another, with his eyes, his host, seeing the muscles of the back of his thin, scraggy neck stand out above his low flannel collar, thought of the ease with which he could squeeze that throat, and the pleasure, the triumphant, lustful pleasure, that such an action would give him.

The low, white-walled, white-ceilinged room was flooded with the mellow, kindly Lakeland sun. October is a wonderful month in the English Lakes, golden, rich, and perfumed, slow suns moving through apricot-tinted skies to ruby evening glories; the shadows lie then thick about that beautiful country, in dark purple patches, in long web-like patterns of silver gauze, in thick splotches of amber and grey. The clouds pass in galleons across the mountains, now veiling, now revealing, now descending with ghost-like armies to the very breast of the plains, suddenly rising to the softest of blue skies and lying thin in lazy languorous colour.

Fenwick’s cottage looked across to Low Fells; on his right, seen through side windows, sprawled the hills above Ullswater.

Fenwick looked at Foster’s back and felt suddenly sick, so that he sat down, veiling his eyes for a moment with his hand. Foster had come up there, come all the way from London, to explain. It was so like Foster to want to explain, to want to put things right. For how many years had he known Foster? Why, for twenty at least, and during all those years Foster had been for ever determined to put things right with everybody. He could never bear to be disliked; he hated that anyone should think ill of him; he wanted everyone to be his friends. That was one reason, perhaps, why Foster had got on so well, had prospered so in his career; one reason, too, why Fenwick had not.

For Fenwick was the opposite of Foster in this. He did not want friends, he certainly did not care that people should like him—that is people for whom, for one reason or another, he had contempt—and he had contempt for quite a number of people.

Fenwick looked at that long, thin, bending back and felt his knees tremble. Soon Foster would turn round and that high, reedy voice would pipe out something about the books. “What jolly books you have, Fenwick!” How many, many times in the long watches of the night, when Fenwick could not sleep, had he heard that pipe sounding close there—yes, in the very shadows of his bed! And how many times had Fenwick replied to it: “I hate you! You are the cause of my failure in life! You have been in my way always. Always, always, always! Patronizing and pretending, and in truth showing others what a poor thing you thought me, how great a failure, how conceited a fool! I know. You can hide nothing from me! I can hear you!”

For twenty years now Foster had been persistently in Fenwick’s way. There had been that affair, so long ago now, when Robins had wanted a sub-editor for his wonderful review, the Parthenon, and Fenwick had gone to see him and they had had a splendid talk. How magnificently Fenwick had talked that day; with what enthusiasm he had shown Robins (who was blinded by his own conceit, anyway) the kind of paper the Parthenon might be; how Robins had caught his own enthusiasm, how he had pushed his fat body about the room, crying: “Yes, yes, Fenwick—that’s fine! That’s fine indeed!”—and then how, after all, Foster had got that job.

The paper had only lived for a year or so, it is true, but the connection with it had brought Foster into prominence just as it might have brought Fenwick!

Then, five years later, there was Fenwick’s novel, The Bitter Aloe—the novel upon which he had spent three years of blood-and-tears endeavour—and then, in the very same week of publication, Foster brings out The Circus, the novel that made his name; although, Heaven knows, the thing was poor enough sentimental trash. You may say that one novel cannot kill another—but can it not? Had not The Circus appeared would not that group of London know-alls—that conceited, limited, ignorant, self-satisfied crowd, who nevertheless can do, by their talk, so much to affect a book’s good or evil fortunes—have talked about The Bitter Aloe and so forced it into prominence? As it was, the book was stillborn and The Circus went on its prancing, triumphant way.

After that there had been many occasions—some small, some big—and always in one way or another that thin, scraggy body of Foster’s was interfering with Fenwick’s happiness.

The thing had become, of course, an obsession with Fenwick. Hiding up there in the heart of the Lakes, with no friends, almost no company, and very little money, he was given too much to brooding over his failure. He was a failure and it was not his own fault. How could it be his own fault with his talents and his brilliance? It was the fault of modern life and its lack of culture, the fault of the stupid material mess that made up the intelligence of human beings—and the fault of Foster.

Always Fenwick hoped that Foster would keep away from him. He did not know what he would not do did he see the man. And then one day, to his amazement, he received a telegram:

Passing through this way. May I stop with you Monday and Tuesday?—Giles Foster.

Fenwick could scarcely believe his eyes, and then—from curiosity, from cynical contempt, from some deeper, more mysterious motive that he dared not analyse—he had telegraphed—Come.

And here the man was. And he had come—would you believe it?—to “put things right”. He had heard from Hamlin Eddis that Fenwick was hurt with him, had some kind of grievance.

“I didn’t like to feel that, old man, and so I thought I’d just stop by and have it out with you, see what the matter was, and put it right.”

Last night after supper Foster had tried to put it right. Eagerly, his eyes like a good dog’s who is asking for a bone that he knows he thoroughly deserves, he had held out his hand and asked Fenwick to “say what was up”.

Fenwick simply had said that nothing was up; Hamlin Eddis was a damned fool.

“Oh, I’m glad to hear that!” Foster had cried, springing up out of his chair and putting his hand on Fenwick’s shoulder. “I’m glad of that, old man. I couldn’t bear for us not to be friends. We’ve been friends so long.”

Lord! How Fenwick hated him at that moment!

II

“What a jolly lot of books you have!” Foster turned round and looked at Fenwick with eager, gratified eyes. “Every book here is interesting! I like your arrangement of them, too, and those open bookshelves—it always seems to me a shame to shut up books behind glass!”

Foster came forward and sat down quite close to his host. He even reached forward and laid his hand on his host’s knee. “Look here! I’m mentioning it for the last time—positively! But I do want to make quite certain. There is nothing wrong between us, is there, old man? I know you assured me last night, but I just want …”

Fenwick looked at him and, surveying him, felt suddenly an exquisite pleasure of hatred. He liked the touch of the man’s hand on his knee; he himself bent forward a little and, thinking how agreeable it would be to push Foster’s eyes in, deep, deep into his head, crunching them, smashing them to purple, leaving the empty, staring, bloody sockets, said:

“Why, no. Of course not. I told you last night. What could there be?”

The hand gripped the knee a little more tightly.

“I am so glad! That’s splendid! Splendid! I hope you won’t think me ridiculous, but I’ve always had an affection for you ever since I can remember. I’ve always wanted to known you better. I’ve admired your talent so greatly. That novel of yours—the—the—the one about the aloe———”

“The Bitter Aloe?“

“Ah yes, that was it. That was a splendid book. Pessimistic, of course, but still fine. It ought to have done better. I remember thinking so at the time.”

“Yes, it ought to have done better.”

“Your time will come, though. What I say is that good work always tells in the end.”

“Yes, my time will come.”

The thin, piping voice went on:

“Now, I’ve had more success than I deserved. Oh yes, I have. You can’t deny it. I’m not falsely modest. I mean it. I’ve got some talent, of course, but not so much as people say. And you! Why, you’ve got so much more than they acknowledge. You have, old man. You have indeed. Only—I do hope you’ll forgive my saying this—perhaps you haven’t advanced quite as you might have done. Living up here, shut away here, closed in by all these mountains, in this wet climate—always raining—why, you’re out of things! You don’t see people, don’t talk and discover what’s really going on. Why, look at me!”

Fenwick turned round and looked at him.

“Now, I have half the year in London, where one gets the best of everything, best talk, best music, best plays; and then I’m three months abroad, Italy or Greece or somewhere, and then three months in the country. Now, that’s an ideal arrangement. You have everything that way.”

Italy or Greece or somewhere!

Something turned in Fenwick’s breast, grinding, grinding, grinding. How he had longed, oh, how passionately, for just one week in Greeee, two days in Sicily! Sometimes he had thought that he might run to it, but when it had come to the actual counting of the pennies … And how this fool, this fat-head, this self-satisfied, conceited, patronizing …

He got up, looking out at the golden sun.

“What do you say to a walk?” he suggested. “The sun will last for a good hour yet.”

III

As soon as the words were out of his lips he felt as though someone else had said them for him. He even turned half round to see whether anyone else were there. Ever since Foster’s arrival on the evening before he had been conscious of this sensation. A walk? Why should he take Foster for a walk, show him his beloved country, point out those curves and lines and hollows, the broad silver shield of Ullswater, the cloudy purple hills hunched like blankets about the knees of some recumbent giant? Why? It was as though he had turned round to someone behind him and had said: “You have some further design in this.”

They started out. The road sank abruptly to the lake, then the path ran between trees at the water’s edge. Across the lake tones of bright yellow light, crocus-hued, rode upon the blue. The hills were dark.

The very way that Foster walked bespoke the man. He was always a little ahead of you, pushing his long, thin body along with little eager jerks, as though, did he not hurry, he would miss something that would be immensely to his advantage. He talked, throwing words over his shoulder to Fenwick as you throw crumbs of bread to a robin.

“Of course I was pleased. Who would not be? After all, it’s a new prize. They’ve only been awarding it for a year or two, but it’s gratifying—really gratifying—to secure it. When I opened the envelope and found the cheque there—well, you could have knocked me down with a feather. You could, indeed. Of course, a hundred pounds isn’t much. But it’s the honour….”

Whither were they going? Their destiny was as certain as though they had no free will. Free will? There is no free will. All is Fate. Fenwick suddenly laughed aloud.

Foster stopped.

“Why, what is it?”

“What’s what?”

“You laughed.”

“Something amused me.”

Foster slipped his arm through Fenwick’s.

“It is jolly to be walking along together like this, arm in arm, friends. I’m a sentimental man. I won’t deny it. What I say is that life is short and one must love one’s fellow-beings, or where is one? You live too much alone, old man.” He squeezed Fenwick’s arm. “That’s the truth of it.”

It was torture, exquisite, heavenly torture. It was wonderful to feel that thin, bony arm pressing against his. Almost you could hear the beating of that other heart. Wonderful to feel that arm and the temptation to take it in your hands and to bend it and twist it and then to hear the bones crack … crack … crack…. Wonderful to feel that temptation rise through one’s body like boiling water and yet not to yield to it. For a moment Fenwick’s hand touched Foster’s. Then he drew himself apart.

“We’re at the village. This is the hotel where they all come in the summer. We turn off at the right here. I’ll show you my tarn.”

IV

“Your tarn?” asked Foster. “Forgive my ignorance, but what is a tarn exactly?”

“A tarn is a miniature lake, a pool of water lying in the lap of the hill. Very quiet, lovely, silent. Some of them are immensely deep.”

“I should like to see that.”

“It is some little distance—up a rough road. Do you mind?”

“Not a bit. I have long legs.”

“Some of them are immensely deep—unfathomable—nobody touched the bottom—but quiet, like glass, with shadows only———”

“Do you know, Fenwick, I have always been afraid of water—I’ve never learnt to swim. I’m afraid to go out of my depth. Isn’t that ridiculous? But it is all because at my private school, years ago, when I was a small boy, some big fellows took me and held me with my head under the water and nearly drowned me. They did indeed. They went farther than they meant to. I can see their faces.”

Fenwick considered this. The picture leapt to his mind. He could see the boys—large, strong fellows, probably—and this skinny thing like a frog, their thick hands about his throat, his legs like grey sticks kicking out of the water, their laughter, their sudden sense that something was wrong, the skinny body all flaccid and still….

He drew a deep breath.

Foster was walking beside him now, not ahead of him, as though he were a little afraid and needed reassurance. Indeed, the scene had changed. Before and behind them stretched the uphill path, loose with shale and stones. On their right, on a ridge at the foot of the hill, were some quarries, almost deserted, but the more melancholy in the fading afternoon because a little work still continued there; faint sounds came from the gaunt listening chimneys, a stream of water ran and tumbled angrily into a pool below, once and again a black silhouette, like a question-mark, appeared against the darkening hill.

It was a little steep here, and Foster puffed and blew.

Fenwick hated him the-more for that. So thin and spare and still he could not keep in condition! They stumbled, keeping below the quarry, on the edge of the running water, now green, now a dirty white-grey, pushing their way along the side of the hill.

Their faces were set now towards Helvellyn. It rounded the cup of hills, closing in the base and then sprawling to the right.

“There’s the tarn!” Fenwick exclaimed; and then added, “The sun’s not lasting as long as I had expected. It’s growing dark already.”

Foster stumbled and caught Fenwick’s arm.

“This twilight makes the hills look strange—like living men. I can scarcely see my way.”

“We’re alone here,” Fenwick answered. “Don’t you feel the stillness? The men will have left the quarry now and gone home. There is no one in all this place but ourselves. If you watch you will see a strange green light steal down over the hills. It lasts for but a moment and then it is dark.

“Ah, here is my tarn. Do you know how I love this place, Foster? It seems to belong especially to me, just as much as all your work and your glory and fame and success seem to belong to you. I have this and you have that. Perhaps in the end we are even, after all. Yes….

“But I feel as though that piece of water belonged to me and I to it, and as though we should never be separated—yes. … Isn’t it black?

“It is one of the deep ones. No one has ever sounded it. Only Helvellyn knows, and one day I fancy that it will take me, too, into its confidence, will whisper its secrets———”

Foster sneezed.

“Very nice. Very beautiful, Fenwick. I like your tarn. Charming. And now let’s turn back. That is a difficult walk beneath the quarry. It’s chilly, too.”

“Do you see that little jetty there?” Fenwick lecf Foster by the arm. “Someone built that out into the water. He had a boat there, I suppose. Come and look down. From the end of the little jetty it looks so deep and the mountains seem to close round.”

Fenwick took Foster’s arm and led him to the end of the jetty. Indeed, the water looked deep here. Deep and very black. Foster peered down, then he looked up at the hills that did indeed seem to have gathered close around him. He sneezed again.

“I’ve caught a cold, I am afraid. Let’s turn homewards, Fenwick, or we shall never find our way.”

“Home, then,” said Fenwick, and his hands closed about the thin, scraggy neck. For the instant the head half turned, and two startled, strangely childish eyes stared; then, with a push that was ludicrously simple, the body was impelled forward, there was a sharp cry, a splash, a stir of something white against the swiftly gathering dusk, again and then again, then far-spreading ripples, then silence.

V

The silence extended. Having enwrapped the tarn, it spread as though with finger on lip to the already quiescent hills. Fenwick shared in the silence. He luxuriated in it. He did not move at all. He stood there looking upon the inky water of the tarn, his arms folded, a man lost in intensest thought. But he was not thinking. He was only conscious of a warm, luxurious relief, a sensuous feeling that was not thought at all.

Foster was gone—that tiresome, prating, conceited, self-satisfied fool! Gone, never to return. The tarn assured him of that. It stared back into Fenwick’s face approvingly as though it said: “You have done well—a clean and necessary job. We have done it together, you and I. I am proud of you.”

He was proud of himself. At last he had done something definite with his life. Thought, eager, active thought, was beginning now to flood his brain. For all these years he had hung around in this place doing nothing but cherish grievances, weak, backboneless—now at last there was action. He drew himself up and looked at the hills. He was proud—and he was cold. He was shivering. He turned up the collar of his coat. Yes, there was that faint green light that always lingered in the shadows of the hills for a brief moment before darkness came. It was growing late. He had better return.

Shivering now so that his teeth chattered, he started off down the path, and then was aware that he did not wish to leave the tarn. The tarn was friendly—the only friend he had in all the world. As he stumbled along in the dark this sense of loneliness grew. He was going home to an empty house. There had been a guest in it last night. Who was it? Why, Foster, of course—Foster with his silly laugh and amiable, mediocre eyes. Well, Foster would not be there now. No, he never would be there again.

And Suddenly Fenwick started to run. He did not know why, except that, now that he had left the tarn, he was lonely. He wished that he could have stayed there all night, but because it was cold he could not, and so now he was running so that he might be at home with the lights and the familiar furniture—and all the things that he knew to reassure him.

As he ran the shale and stones scattered beneath his feet. They made a tit-tattering noise under him, and someone else seemed to be running too. He stopped, and the other runner also stopped. He breathed in the silence. He was hot now. The perspiration was trickling down his cheeks. He could feel a dribble of it down his back inside his shirt. His knees were pounding. His heart was thumping. And all around him the hills were so amazingly silent, now like india-rubber clouds that you could push in or pull out as you do those india-rubber faces, grey against the night sky of a crystal purple, upon whose surface, like the twinkling eyes of boats at sea, stars were now appearing.

His knees steadied, his heart beat less fiercely, and he began to run again. Suddenly he had turned the corner and was out at the hotel. Its lamps were kindly and reassuring. He walked then quietly along the lake-side path, and had it not been for the certainty that someone was treading behind him he would have been comfortable and at his ease. He stopped once or twice and looked back, and once he stopped and called out, “Who’s there?” Only the rustling trees answered.

He had the strangest fancy, but his brain was throbbing so fiercely that he could not think, that it was the tarn that was following him, the tarn slipping, sliding along the road, being with him so that he should not be lonely. He could almost hear the tarn whisper in his ear: “We did that together, and so I do not wish you to bear all the responsibility yourself. I will stay with you, so that you are not lonely.”

He climbed down the road towards home, and there were the lights of his house. He heard the gate click behind him as though it were shutting him in. He went into the sitting-room, lighted and ready. There were the books that Foster had admired.

The old woman who looked after him appeared.

“Will you be having some tea, sir?”

“No, thank you, Annie.”

“Will the other gentleman be wanting any?”:

“No; the other gentleman is away for the night.”

“Then there will be only one for supper?”

“Yes, only one for supper.”

He sat in the corner of the sofa and fell instantly into a deep slumber.

VI

He woke when the old woman tapped him on the shoulder and told him that supper was served. The room was dark save for the jumping light of two uncertain candles. Those two red candlesticks—how he hated them up there on the mantelpiece! He had always hated them, and now they seemed to him to have something of the quality of Foster’s voice—that thin, reedy, piping tone.

He was expecting at every moment that Foster would enter, and yet he knew that he would not. He continued to turn his head towards the door, but it was so dark there that you could not see. The whole room was dark except just there by the fireplace, where the two candlesticks went whining with their miserable twinkling plaint.

He went into the dining-room and sat down to his meal. But he could not eat anything. It was odd—that place by the table where Foster’s chair should be. Odd, naked, and made a man feel lonely.

He got up once from the table and went to the window, opened it and looked out. He listened for something, A trickle as of running water, a stir, through the silence, as though some deep pool were filling to the brim. A rustle in the trees, perhaps. An owl hooted; Sharply, as though someone had spoken unexpectedly behind his shoulder, he closed the windows and looked back, peering under his dark eyebrows into the room.

Later on he went up to his bed.

VII

Had he been sleeping, or had he been lying lazily, as one does, half dozing, half luxuriously not thinking? He was wide awake now, utterly awake, and his heart was beating with apprehension. It was as though someone had called him by name. He slept always with his window a little open and the blind up. To-night the moonlight shadowed in sickly fashion the objects in his room. It was not a flood of light nor yet a sharp splash, silvering a square, a circle, throwing the rest into ebony darkness. The ught was dim, a little green, perhaps, like the shadow that comes over the hills just before dark.

He stared at the window, and it seemed to him that something moved there. Within, or rather against, the green-grey light, something silver-tinted glistened. Fenwick stared. It had the look, exactly, of slipping water.

Slipping water! He listened, his head up, and it seemed to him that from beyond the window he caught the stir of water, not running, but rather welling up and up, gurgling with satisfaction as it filled and filled.

He sat up higher in bed, and then saw that down the wallpaper beneath the window water was undoubtedly trickling. He could see it lurch to the projecting wood of the sill, pause, and then slip, slither down the incline. The odd thing was that it fell so silently.

Beyond the window there was that odd gurgle, but in the room itself absolute silence. Whence could it come? He saw the line of silver rise and fall as the stream on the window-ledge ebbed and flowed.

He must get up and close the window. He drew his legs above the sheets and blankets and looked down.

He shrieked. The floor was covered with a shining film of water. It was rising. As he looked it had covered half the short stumpy legs of the bed. It rose without a wink, a bubble, a break! Over the sill it poured now in a steady flow, but soundless. Fenwick sat up in the bed, the clothes gathered up to his chin, his eyes blinking, the Adam’s apple throbbing like a throttle in his throat.

But he must do something, he must stop this. The water was now level with the seats of the chairs, but still was soundless. Could he but reach the door!

He put down his naked foot, then cried again. The water was icy cold. Suddenly, leaning, staring at its dark, unbroken sheen, something seemed to push him forward. He fell. His head, his face was under the icy liquid; it seemed adhesive and, in the heart of its ice, hot like melting wax. He struggled to his feet. The water was breast-high. He screamed again and again. He could see the looking-glass, the row of books, the picture of Dürer’s “Horse”, aloof, impervious. He beat at the water, and flakes of it seemed to cling to him like scales of fish, clammy to his touch. He struggled, ploughing his way towards the door.

The water now was at his neck. Then something had caught him by the ankle. Something held him. He struggled, crying: “Let me go! Let me go! I tell you to let me go! I hate you! I hate you! I will not come down to you! I will not———”

The water covered his mouth. He felt that someone pushed in his eyeballs with bare knuckles. A cold hand reached up and caught his naked thigh.

VIII

In the morning the little maid knocked and, receiving no answer, came in, as was her wont, with his shaving-water. What she saw made her scream. She ran for the gardener.

They took the body with its staring, protruding eyes, its tongue sticking out between the clenched teeth, and laid it on the bed.

The only sign of disorder was an overturned water-jug. A small pool of water stained the carpet.

It was a lovely morning. A twig of ivy idly, in the little breeze, tapped the pane.